AI coding tool limitations

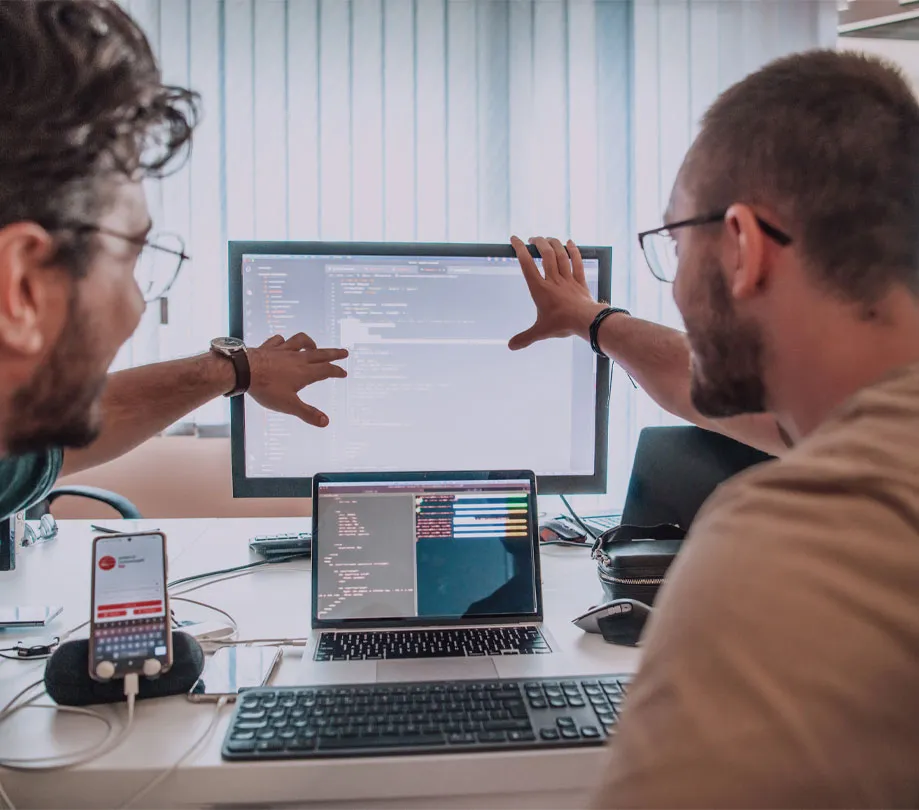

Even though developers rely on AI assistants to boost productivity, the reality is that AI coding tool limitations still prevent these systems from fully understanding project structure, maintaining long-term context, or reasoning across complex tasks.

Artificial intelligence tools that write code are now built into the daily workflows of most developers. In 2025, nearly 82% of programmers reported using AI-assisted coding tools every week, and more than half of them are juggling three or more AI assistants at once. The benefits are clear in terms of speed and convenience. But when it comes to full software engineering, the real work of designing, maintaining, and shipping complex systems, AI still falls short. That’s the takeaway from a new research project by MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab (CSAIL), with input from Stanford, Berkeley, and Cornell. The findings were presented at the International Conference on Machine Learning this month and challenge some assumptions about where AI is headed in coding.

AI coding tools are everywhere, but they aren’t replacing software engineers

The study focused on something called "long-horizon code planning." This refers to how software engineers think across many steps to design and build programs that work across teams, features, and platforms. It’s not just about typing out the correct syntax, it’s about understanding tradeoffs, system requirements, code quality, performance, memory constraints, and user needs. That’s something AI struggles to do.

MIT PhD candidate Alex Gu, one of the study’s authors, gave an example: designing a new programming language. It’s not just writing functions or picking syntax. It means thinking about who will use the language, what kind of API surface makes sense, how developers will call and extend it, and what long-term support looks like. These are not simple code-generation tasks, they are design and architecture decisions that involve judgment, tradeoffs, and conversation.

AI models, even those trained on massive datasets of code, usually don’t do this kind of deep reasoning well. They can generate small snippets quickly, but they don’t have memory across time or a model of how a software project evolves.

AI benchmarks are too simple

Part of the issue lies in how AI is evaluated. Most AI coding benchmarks focus on short tasks, like solving toy problems, writing single functions, or producing basic outputs from natural language prompts. But software engineering isn’t a series of isolated puzzles.

Gu pointed out that real-world work includes testing, debugging, documentation, collaborating with others, and maintaining code across years. These tasks don’t show up in benchmarks, so it’s unclear how AI handles them.

Even within coding tasks, AI performs best on things it has already seen. If a code problem is similar to something in the training data, the model usually does fine. But when working in lesser-used languages, legacy systems, or custom libraries, performance drops. Scientific computing, embedded firmware, and internal company tools are some examples where AI often struggles. That’s because the model can’t generalize well to new domains with sparse training data.

Understanding the codebase

Another challenge is how AI systems think about a project over time. Humans build mental models of software systems, how files are organized, which functions call which, where bugs tend to appear, what parts are legacy, what’s been recently updated. These models evolve as the project changes.

AI tools don’t have persistent memory across prompts. They can’t remember what you changed yesterday or why you made a specific decision last week. There’s no built-in model of the software’s architecture or history.

To work well in big codebases, AI would need three things:

- A clear picture of how the project is structured.

- An understanding of how the parts fit together and depend on each other.

- The ability to update its mental model as new code is added or changed.

Right now, most tools don’t do that. They work on one file or function at a time. Without memory or context, their usefulness in large projects is limited.

Intent matters

Another weakness of current AI coding tools is inferring intent. A software engineer knows that a website for a local business should be more secure and robust than one built for a coding demo or personal project. That context affects design decisions, architecture, and priorities.

AI models don’t have a strong sense of intent. They can generate code that looks fine, but it might not match the actual needs of the user or project. This makes them less useful in settings where precision, domain knowledge, or user-specific constraints matter.

Where AI helps today

- Despite these gaps, AI is helping developers every day in real ways:

- Writing boilerplate code

- Generating test cases

- Fixing basic bugs

- Offering syntax suggestions

- Converting code between languages

- Creating small utilities or scripts

In education, AI has been especially helpful. It can grade homework, write practice problems, and walk students through explanations of math or computer science questions. These are narrow but useful tasks, and they free up time for teachers and developers to focus on harder problems.

What comes next

The MIT team sees room for progress. One step is creating better benchmarks that reflect real work, testing, collaboration, legacy support, intent matching, and project-wide understanding. These would give researchers and tool builders a better sense of what matters.

There’s also interest in AI tools that act more like collaborators. That means models that can ask clarifying questions, remember past decisions, and adjust suggestions based on user feedback. None of that is common yet, but it’s a possible direction.

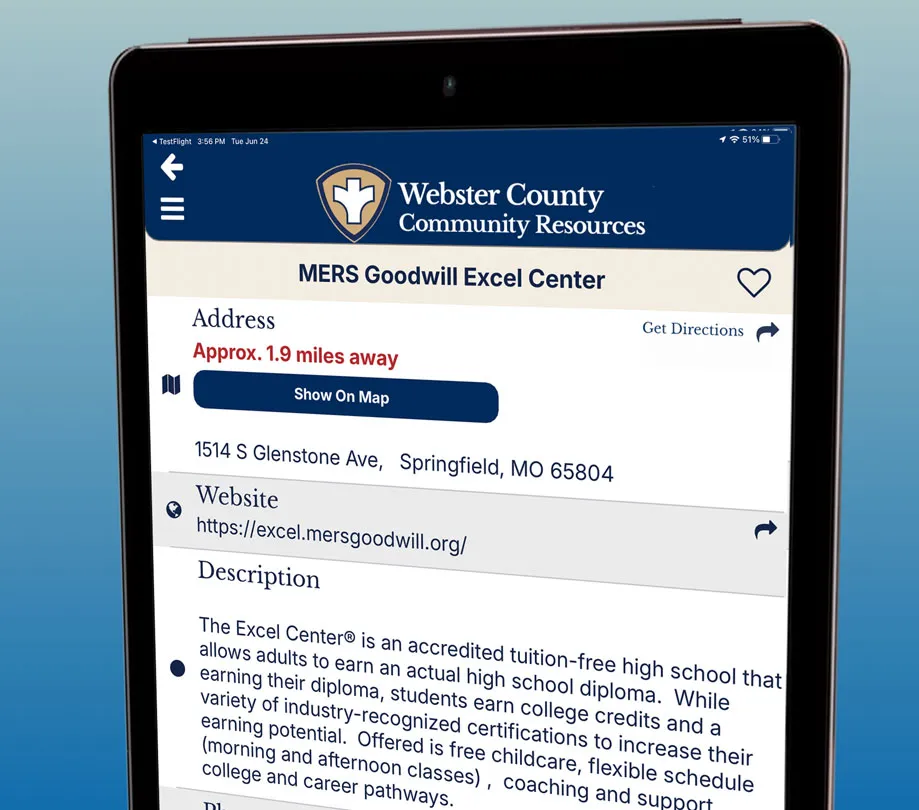

For teams like ours, the message is clear: AI coding tools can speed up the basics, but they’re not project leads. They don’t replace system architects, senior developers, or the people who understand users and business goals. They’re good assistants, not engineers. As we continue to build and release apps, plugins, and custom software systems, we’ll keep using AI tools, but we’ll also keep doing the tasks, programming, architecting, thinking and planning they can’t do.

About the Author

CEO

Richard Harris is widely regarded as a pioneer in the software industry, with over 30 years of experience as a founder, executive leader, and technology strategist. Throughout his career, he has launched and scaled numerous ventures across mobile, SaaS, publishing, and data intelligence. Richard is the founder of App Developer Magazine, Chirp GPS, MarketByte, and several other startups—each focused on solving real-world challenges through innovative, developer-centric solutions. He has spent decades architecting scalable platforms and building infrastructure that powers digital growth—from real-time location intelligence to content syndication engines. Whether streamlining developer workflows, modernizing logistics, or enabling cross-channel marketing automation, Richard’s leadership continues to drive operational clarity and product excellence in a rapidly evolving tech landscape.